Científicos del Centro Nacional de Investigaciones Oncológicas (CNIO) han descubierto que el gen NANOG, una pieza fundamental en la pluripotencia de las células madre de los embriones, regula también la división de las células adultas en los epitelios estratificados, aquellos que forman parte de la epidermis de la piel o recubren el esófago o la vagina.

Según las conclusiones del estudio, recogido en la revista 'Nature Communications', este factor podría también participar en la formación de tumores derivados de los epitelios estratificados, como los del esófago, cabeza o cuello.

Hasta la fecha se sabía que el factor de pluripotencia NANOG estaba activo durante tan solo dos días del desarrollo embrionario humano, aquellos previos a la implantación del embrión en el útero materno (entre los días 5 y 7 después de la fecundación). Durante este período crítico del desarrollo contribuye a que las células madre del embrión adquieran una amplísima capacidad de especialización que las convertirá en todos y cada uno de los tejidos que formarán el embrión.

Ahora un estudio del CNIO encabezado por Manuel Serrano y Daniela Piazzolla demuestra que NANOG también tiene actividad en el organismo adulto, más allá de su función durante este breve periodo del desarrollo embrionario.

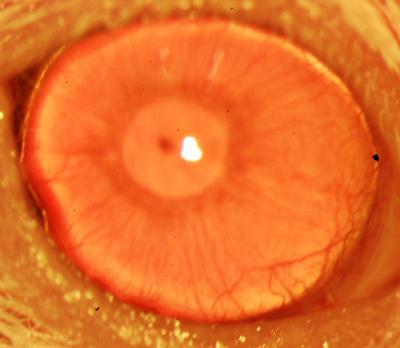

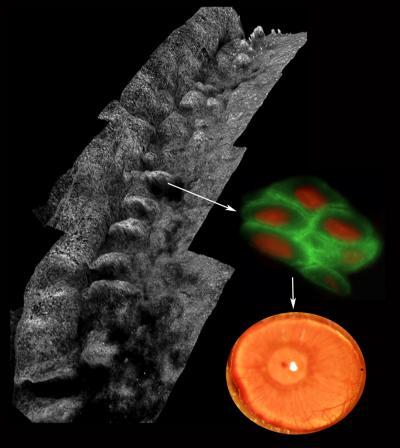

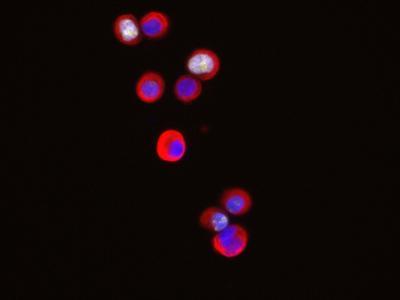

Después de analizar mediante inmunohistoquímica la presencia de NANOG en los distintos tejidos de ratón, el equipo del CNIO ha constatado que este factor está presente en epitelios adultos estratificados como los del esófago, piel o vagina.

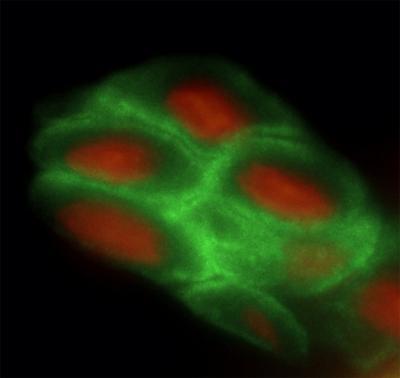

Para ello, estudiaron estirpes de ratón que permiten inducir el factor NANOG de una forma programada y limitada en el tiempo. Y según describe el artículo, el aumento de NANOG en estos ratones produce un incremento en la proliferación de las células, hiperplasia, y un aumento en el daño del ADN celular.

"Estos efectos solo se manifiestan en los epitelios estratificados, mientras que otros tejidos, como el hígado o el riñón, son indiferentes a la presencia de NANOG", ha explicado Serrano.

Estos resultados indican que hay una selectividad en los efectos de NANOG que solo se manifiestan en los epitelios estratificados. "A través de análisis globales del genoma demostramos que este factor es capaz de regular específicamente la proliferación de estos tejidos, y lo hace a través de la proteína AURKA, que está involucrada en el control de la división celular", ha añadido.

Los autores del trabajo también demuestran que NANOG está aumentado en tumores de pacientes derivados de epitelios estratificados. Además, cuando bloquearon la acción del gen mediante ARNs de interferencia el índice de proliferación de las células disminuyó.

"Esto nos indica que estas células cancerosas dependen de la actividad de NANOG para mantener su alta tasa proliferativa y sus propiedades oncológicas", según Serrano.